The Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens (AP) has issued guidance on how websites should seek consent if they use cookie banners (1). Among other things, the AP prescribes that websites should offer the choice to refuse or accept cookies on one layer. Some cookie banners contain a button to accept the storage of cookies and a button giving the data subject access to further options, but without the option to directly reject all cookies. This option is only found in the second layer. According to the AP, this does not meet its stated requirement that accepting and refusing cookies should be equally easy. In this blog, we examine whether the requirement formulated by the AP follows from the AVG.

A cookie is a small file that can be placed on visitors' devices when visiting websites. There are different types of cookies with different purposes. Functional cookies are necessary for the effective functioning of a service or webshop. Think, for example, of keeping track of products you have added to the shopping cart. Analytical cookies are used by a website, for example, to keep track of the number of visitors. Tracking cookies track people's Internet behavior.

Cookie legislation in the Netherlands can be found in Article 11.7a of the Telecommunications Act. This article is based on the e-Privacy Directive (Directive 2002/58/EC). Functional and analytical cookies generally have limited impact on privacy. These cookies can then be placed automatically when visiting a website, a visitor does not need to give permission. In other cases, such as tracking cookies, placement is only allowed if prior consent is obtained. Articles 4(11), Article 7 and recitals 32, 42 and 43 AVG (Regulation 2016/679 EU) contain requirements with which data subject consent must comply:

Consent must be freely given (Article 4(11) and Recital 42 AVG);

Consent must be specific (Article 4(11) AVG);

Consent must be informed (Article 4(11) AVG);

Consent must be an unambiguous expression of will by which the data subject accepts, by means of a statement or an unambiguous act, the processing of personal data concerning him. This means that consent must be explicitly given through a positive act. The use of ticked check boxes is thus not allowed (Article 4(11) AVG);

The controller must be able to demonstrate consent (Article 7(1) AVG);

Consent must be presented in clear and simple language so that a clear distinction can be made from another matter (Article 7(2) AVG);

Separate consent must be possible for different personal data processing operations (Recital 43 AVG, the "granularitet" requirement);

Consent must be revocable at any time; withdrawing consent must be as simple as giving it (Article 7(3) AVG).

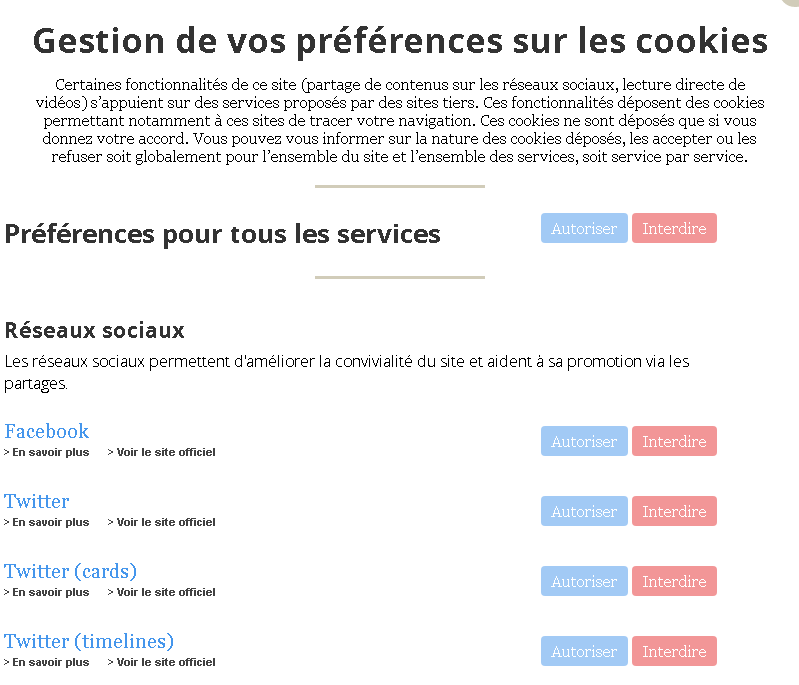

The new guidance would mean that a construction such as that used by the French regulator CNIL in the past, and still used by many organizations today, would no longer be allowed.

In this construct, the first layer asks for permission ("OK, tout accepter") with the option to click through to a second layer for personalized settings ("personalizer").

![]()

The second layer then contains the ability to set the settings for each type of cookie. If all goes well, in this second layer the cookies requiring consent are "off" and an active action is required to activate them. CNIL had designed this second layer as follows:

In this design, on the second layer, all cookies can be refused, or each cookie can be chosen to accept or refuse. The cookie settings page can also always be visited later to change the choice.

In our view, this construction fulfills all the requirements of the AVG for legally valid consent, especially the requirement of granularity and the requirement that consent can also be easily withdrawn.

However, the AP informs in the guidance that it is not allowed to ask for consent in the cookie banner, and only in a second layer to offer an option with refuse/reject/disagree cookies. From now on, this option must be available on the same layer as the layer for which consent is sought.

The January 17, 2024 report of the European Data Protection Board's Cookie Banner Taskforce suggests that a majority of European privacy regulators believe that there is a breach of the e-Privacy Directive when a banner does not provide options to accept or reject cookies on the same layer (2). However, some regulators believe that there is no breach due to the lack of an explicit "reject option" for setting cookies under Article 5(3) of the e-Privacy Directive.

We do not encounter the requirement set forth by the AP in either the AVG or the Telecommunications Act. We wonder - with the minority of privacy regulators from the EDPB - what this requirement can be based on.

According to the AP, the obligation follows from its stated rule that refusing consent must be as simple as accepting it. However, that rule does not appear in the AVG. Article 7(3) AVG does state that withdrawing consent must be as simple as giving it; however, withdrawal is different from refusal (3).

The next question that can be asked is whether offering a reject cookies button in the second layer detracts from free consent. Does providing an additional click detract from the nature of free consent?

On April 17, the EDPB issued an opinion on valid consent in the context of consent or pay models (also known as "consent or pay" models) implemented by major online platforms. This was prompted by a request from the Dutch, German and Norwegian data protection authorities. In para. 67 of this opinion, the EDPB states that data controllers should not limit data subjects' autonomy by making it more difficult to refuse consent than to give consent. However, as noted above, this is not a requirement that follows from the AVG. The fact that the user must click through to set cookie choices does not, in our opinion, in a general sense make giving consent no longer a free choice.

We then considered whether the requirement formulated by the AP could follow from Article 25(2) AVG (data protection by default). We believe that it does not. It follows from Article 25(2) AVG that consent-dependent cookies may be placed only after consent has been given, not that a refuse button must be placed on the same layer as the consent request itself.

At the European level, there are several regulations that discuss deceptive design patterns (also known as dark patterns), including the AVG, the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (Directive 2005/29), the Digital Services Act (Regulation 2001/31), the Digital Markets Act (Directive 2022/1925), the Data Act (Regulation 2023/2854) and the Artificial Intelligence Act (COM (2021) 2016 final). The EDPB has issued Guidance on deceptive design patterns.

According to the EDPB Guidelines, deceptive design patterns are interfaces on social media platforms, websites or in cookie banners that cause users to make unintentional, often unwilling and/or potentially harmful decisions regarding personal data that are in the best interest of the social media platform. Misleading design patterns fall into several categories. One of the forms in which this can take place is so-called "obstructing. This occurs when users are hindered or blocked in their process of getting information or managing their data by making the action difficult or impossible. Users then want to perform a particular action related to their data protection, and that user journey is presented in such a way that it requires more steps than necessary for the activation of options that infringe on that person's data. This then has the effect of likely discouraging users from activating such a control (4).

The EDPB Guidelines cite an example of users who click the "skip" button during the sign-up process (to avoid seeing certain data) are presented with a pop-up window asking "Are you sure?" By questioning their decision, the social media provider prompts users to reconsider their decision and disclose certain data, such as gender, contact list or photo. In contrast, users who choose to enter the data directly do not see a message asking them to reconsider their choice (5).

Early this year, the AP had fined Uber Technologies Inc. and Uber B.V. (Uber) 10 million euros. Uber acted in violation of Article 12 second paragraph AVG by making it unnecessarily difficult for drivers to request to view or receive their data. There was a digital form available in the app for drivers to request access, but this form was difficult to find because it was hidden in various menus and could have been placed in a more logical location and required a large number of steps (7 in total) to get to the form. Although the AP does not refer to this doctrine, this could be seen as an example of a misleading design pattern.

We believe that offering a cookie reject button in the second layer in a clear structure, where the reject button is already found with one additional step, cannot be equated with what is seen as a misleading design pattern.

In our analysis, when the decline button is placed in a second layer, no violation of the directly applicable AVG provisions is found. It is unlikely that this practice would suddenly be prohibited via the detour of the Guidelines on Misleading Design Patterns. This, of course, depends on the further design of the consent texts.

We take into account that the requirements for cookie consent, and consent under the AVG in general, have been elaborated in great detail in the regulations and it may be assumed that a processing that meets these detailed requirements is lawful. The new requirement imposed by the AP, which differs from the interpretation of the relevant legislation as it has been used for years, requires a legislative amendment and cannot be introduced by regulators on the basis of reference to proprietary and general legal principles (6).

The newly worded requirement from the AP's guidance, to the effect that accept should be as easy as reject, cannot in our view be seen as a general rule that follows from legislation such as the e-Privacy Directive, the Telecommunications Act, the DSA or the AVG. Under circumstances, it could perhaps be argued that offering cookie banners that include a button to accept the storage of cookies and include a button allowing the data subject to access further options could qualify as a misleading design pattern. This depends on the design of the whole, including wording used, and cannot be seen as a general rule that follows from the legislation.

In view of the above, we think that a fine decision based on the general rule that the option to refuse cookies must be offered on the same layer as the option to accept cookies should not stand up in court. Meanwhile, a prudent data controller will have to take into account this new position of the AP and consider adjusting its website accordingly.

(1) See: https://www.autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/themas/internet-slimme-apparaten/cookies/heldere-en-misleidende-cookiebanners.

(2) EDPB Report of the work undertaken by the Cookie Banner Taskforce, adopted on January 17, 2023, p. 4-5, see: https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/202301/edpb_20230118_report_cookie_banner_taskforce_en.pdf/.

(3) Opinion 08/2024 on Valid Consent in the Context of Consent or Pay Models Implemented by Large Online Platforms, Adopted on April 17, 2024. In para. 68, the EDPB also equates the two requirements without further substantiation.

(4) EDPB Guidelines 03/2022 on deceptive design patterns in social media platform interfaces: how to recognize and avoid them, version 2.0, adopted February 14, 2023, p. 68, see: https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2023-02/edpb_03-2022_guidelines_on_deceptive_design_patterns_in_social_media_platform_interfaces_v2_en_0.pdf

(5) EDPB Guidelines 03/2022 on deceptive design patterns in social media platform interfaces: how to recognize and avoid them, version 2.0, adopted February 14, 2023, p. 21.

(6) Cf. Conseil d'Etat March 27, 2020, 399922, ECLI:FR:CECHR:2020:399922.20200327, JBP 2020/97, with note J.A.N. Baas.