Central banks are considering issuing Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) because of the rise of digital payments and the decline of cash. A major concern regarding CBDCs is user privacy, as some categories of CBDCs may record data and potentially violate the anonymity of transactions. The question remains whether CBDCs actually offer benefits to users compared to cash. In this article, Jorie Corten (Watsonlaw) explores these legal issues.

Digitalization in payments has created unprecedented momentum. Cash is being used less and less, and the corona crisis has added to this (1). These developments and the increasing number of new digital assets entering the market sounded the alarm among central banks to start thinking seriously about the digitization of public money, also known as Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) (2). By now, 90% of the world's central banks are already working on this issue (3). The European Union has also begun to consider digital euros (4).

CBDC refers to a digital form of fiat public money issued and backed by a central bank (5). Depending on the purpose of the issuing entity, the technical definition of CBDC may vary (6).

II.I Differentiations

CBDC differs from the digital form of private money. Private money is money held in accounts with commercial banks. This traditional form of money represents the obligations of a private commercial bank (7). CBDC, on the other hand, is an obligation of a public central bank (8).

Moreover, CBDC differs from stablecoins (9) and crypto-assets (10). Crypto-assets are not backed by or tied to a legal tender (11), nor are all crypto-assets or stablecoins issued by an identifiable central party. In contrast, CBDC is tied to a legal tender and is issued by a central entity (12).

II.II Design categories

Depending on the purpose, CBDCs can be further classified into different categories (13).

II.II.I Wholesale trade (wholesale) vs. retail trade (retail)

Wholesale CBDCs are designed for transaction settlement or large interbank payments and have limited access to banks and other financial institutions (14). Retail CBDCs, on the other hand, are used when the CBDC is intended to be offered to the general public (15). As such, CBDC offers the general public a new way to store money and may be intended to replace existing payment instruments, such as cash or debit cards (16). CBDC differs from cash because it comes in a digital form, as opposed to physical coins and banknotes (17).

II.II.II Account-based vs. Token-based(18)

Account-based CBDCs refer to CBDCs that are connected to an identification system, such as European Digital Identity, and require users to log in before accessing them (19). Therefore, users must undergo verification before they can access and use CBDCs, and lack the features of cash (20). In contrast, token-based CBDCs refer to tokens that are protected by passwords, such as digital signatures, and can be accessed pseudonymously (21). As a result, they have more characteristics of cash or Bitcoin (22).

Digitalization of payment methods has led to new challenges in the monetary system worldwide. Four developments can be distinguished that have led to this disruption (23). First, the rapid increase in interest in crypto-assets that compete with traditional forms of assets (24). Second, the emergence of stablecoins issued by the private sector (25). Third, the entry of big tech into payments and the disruption by platform-based business models (26). And finally, the Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital payment technologies (27).

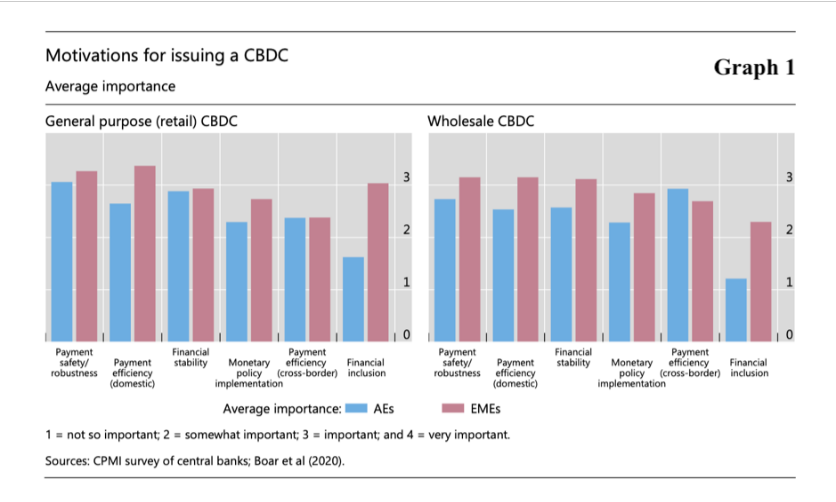

In addition to general global trends, motivations for CBDCs are also driven by national circumstances (28). A survey of central banks shows that in advanced economies, CBDCs are studied by central banks to support the safety and robustness, or efficiency, of domestic payments (see Graph 1).

In addition to general global trends, motivations for CBDCs are also driven by national circumstances (28). A survey of central banks shows that in advanced economies, CBDCs are studied by central banks to support the safety and robustness, or efficiency, of domestic payments (see Graph 1).

Regardless of the design of CBDCs, several legal challenges arise (29), of which privacy issues stand out (30).

IV.I Privacy issues

Through the retail account-based CBDC, the issuing central bank can record, observe and even control the flow of their currency (31). Each transaction is completed and recorded digitally because users must log into a system that must verify their identity, which violates users' privacy (32).

IV.I.I Europe

The Eurogroup emphasized that the digital euro can only succeed if user confidence is guaranteed and maintained, "for which privacy is an important dimension and a fundamental right" (33). The importance of privacy, similar to the privacy of cash today, was emphasized by the Digital Euro Association (34). While the European Central Bank (ECB) generally adheres to these principles and prioritizes privacy, it employs a different strategy that offers citizens much less privacy. The ECB states, "(...), a digital euro would offer a level of privacy equal to that of current digital solutions in the private sector." Thus, the digital euro would have a level of privacy comparable to existing digital payments and not to cash payments (35).

Theoretically, the ECB could address this privacy issue by maintaining anonymity by not verifying the identity of users when they are accessed.(36) While this is currently the case for cash, European regulations do not allow anonymity in electronic payments to prevent money laundering, terrorist financing, tax fraud and evasion of sanctions (37).

The programmability of CBDC poses an even more complicated problem. Although Fabio Panetta recently stated that the digital euro, Europe's CBDC, will be introduced in a form that does not use programmability - due to its nature - it may still be possible to modify it later (38). The tiger resists eating meat for a while before giving in and eating a big chunk when tempted. Similarly, the ECB maintains a privacy-friendly digital currency for a while, but if it is tempted, it may reprogram the terms.

This raises the key question of this article: What is the benefit to citizens of using the digital euro instead of cash if it is inherently programmable and not anonymous?

The rise of digitization in payment systems and the declining use of cash have prompted central banks to consider issuing CBDCs. While CBDCs can offer benefits in principle, there are also legal challenges, particularly in the area of privacy. The design of CBDCs will play a crucial role in addressing these challenges. While the EU and other central banks continue to explore the potential of CBDCs, it is essential that they prioritize user privacy and maintain public trust.

1. De Nederlandsche Bank. (2020). Central Bank Digital Currency. In Objectives, Preconditions and Design Choices. Accessed March 29, 2023, from https://www.dnb.nl/media/espadbvb/central-bank-digital-currency.pdf.

2. Mallekoote, P.M. (2023). Is the digital euro an asset for society? Journal of Financial Law, no. ½, UDH:FR/17563.

3. For an interactive and dashboard-like track that shows worldwide CBDC status, see CBDC Tracker, https://cbdctracker.org/ (last visited Mar. 25, 2023); Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures. (2018). Central bank digital currencies. Bank for International Settlements. Accessed March 26, 2023, from https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d174.html; Todd, R., & Rogers, M. (2020). A global look at central bank digital currencies: From iteration to implementation. The Block Crypto. E-source: https://www.theblockcrypto.com/post/75022/a-global-look-at-central-bank-digitalcurrencies-full-research-report.

4. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing the digital euro. Accessed August 8, 2023, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/NL/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52023PC0369; Eurogroup. (Jan. 16, 2023). Eurogroup Statement on the Digital Euro Project (press release). https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/01/16/eurogroup-statement-on-the-digital-euro-project-16-january-2023/. (Hereinafter: Eurogroup (2023)).

5. Appendino, M., Bespalova, O., Bhattacharya, R., Clevy, J. F., Geng, N., Komatsuzaki, T., ... & Yakhshilikov, Y. (2023). Crypto Assets and CBDCs in Latin America and the Caribbean: Opportunities and Risks. IMF Working Papers, 2023(037), p. 4. (Hereinafter: Appendino et al (2023)).

6. Lee, Y., Son, B., Park, S., Lee, J., & Jang, H. (2021). A Survey on Security and Privacy in Blockchain-based Central Bank Digital Currencies. J. Internet Serv. Inf. Secur., 11(3), p. 16.

7. Boar, C., & Wehrli, A. (2021). Ready, steady, go? - Results on the third BIS survey on central bank digital currency. Bank for International Settlements. Accessed March 27, 2023, from https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap114.pdf, p. 4. (Hereinafter Boar & Wehrli (2021)).

8. Ibid.

9. For example: Tether

10. For example: Bitcoin and Ether.

11. Tsang, C. Y., Yang, A. Y. P., & Chen, P. K. (2022). Disciplining Central Banks: Addressing the Privacy Concerns of CBDCs and Central Bank Independence, p. 8, 9. (Hereinafter: Tsang et al (2022)).

12. Ibid.

13. It is important to keep in mind that this paper focuses only on wholesale versus retail and on account-based versus token-based CBDCs. There are many other design options with their own privacy issues. Other categories include centralized versus decentralized, Tier-1 versus Tier-2, direct versus indirect and interest-bearing versus non-interest-bearing. See, for example: Tsang et al (2022), pp. 8-13.

14. Tsang et al (2022), p. 9; (Boar & Wehrli (2021), p. 4; Bech, M, J Hancock, T Rice and A Wadsworth (2020): "On the future of securities settlement," BIS Quarterly Review, March, pp. 67-83; Appendino et al (2023), p. 4.

15. Boar & Wehrli (2021), p. 4; Appendino et al (2023), p. 4; Bossu, W., Itatani, M., Margulis, C., Rossi, A., Weenink, H., & Yoshinaga, A. (2020). Legal aspects of central bank digital currency: Central bank and monetary law considerations, p. 10.

16. Boar & Wehrli (2021), p. 4; Tsang et al (2022), p. 9.

17. Boar & Wehrli (2021), p. 4.

18. Bank for International Settlements. (2021). Annual Economic Report 2021. Accessed March 27, 2023, from https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2021e.pdf, p. 77-80. (Hereinafter BIS (2021)).

19. European digital identity is still in the research phase, but is expected to be a prerequisite for the digital euro to work, see for example: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/european-digital-identity_en; BIS (2021), p. 91.

20. Tsang et al (2022), p. 9. Didenko, A. N., Zetzsche, D. A., Arner, D. W., & Buckley, R. P. (2020). After Libra, Digital Yuan and COVID-19: Central Bank digital currencies and the new world of money and payment systems, p. 30. (Hereinafter: Didenko et al (2020)).

21. Central banks can further design token-based CBDC into different degrees of pseudonymously, see Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures. (2018). Central bank digital currencies. Bank for International Settlements. Accessed March 26, 2023, from https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d174.html, p. 6; Bank for International Settlements. (2021). Annual Economic Report 2021. Accessed March 27, 2023, from https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2021e.pdf, p. 92.

22. Didenko et al (2020), p. 30.

23. Auer, R., Frost, J., Gambacorta, L., Monnet, C., Rice, T., & Shin, H. S. (2022). Central bank digital currencies: motives, economic implications, and the research frontier. Annual review of economics, 14, 697-721, p. 6. (Hereinafter: Auer et al (2022)).

24. An important note is that crypto-assets are speculative assets rather than money. They are extremely volatile, making it difficult to use them as currency. Therefore, crypto-assets do not necessarily compete with traditional money. See, for example, Carstens, A. (2019): The future of money and payments. Speech held in Dublin, March 22, 2019.

25. Auer et al (2022), p. 7.

26. Bank for International Settlements. Annual Economic Report 2020: III. Central banks and payments in the digital era. (2020). Accessed March 27, 2023, from https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2020e3.html; Shin, H. S. (June 19, 2021). Central bank digital currencies: an opportunity for the monetary system. In speech on the occasion of the BIS Annual General Meeting, Basel (Vol. 29).

27. Saka, O., Eichengreen, B., & Aksoy, C. G. (2021). Epidemic exposure, fintech adoption, and the digital divide (No. w29006). National Bureau of Economic Research.

28. Auer et al (2022), pp. 7-8.

29. For example: the substitution effect on bank deposits which causes safety and stability concerns of the financial system, cybersecurity incidents which causes resilience concerns, and criminal use for money laundering and terrorist finance which raises crime prevention concerns. See e.g. Crawford, J., Menand, L., & Ricks, M. (2021). FedAccounts: Digital Dollars. Geo. Wash. L. Rev., 89, 113; Li, J. (July 21, 2022). There are already counterfeit wallets of China's digital yuan. Quartz. https://qz.com/1922648/there-are-already-counterfeit-wallets-of-chinas-digital-yuan; Ledger Insights. (Nov. 15, 2021). China catches fraudsters using central bank digital currency for money laundering. Ledger Insights - Blockchain for Enterprise. https://www.ledgerinsights.com/china-catches-fraudsters-central-bank-digital-currency-cbdc-for-money-laundering/; Kosuke Takami, N. (June 4, 2021). China's bid for digital-yuan sphere raises red flags at G-7. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Cryptocurrencies/China-s-bid-for-digital-yuan-sphere-raises-red-flags-at-G-7.

30. See, e.g., Privacy Concerns Loom Large as Governments Respond to Crypto. (April 20, 2022). World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/04/privacy-concerns-loom-large-as-governments-respond-to-crypto; Schickler, J. (April 4, 2022). Europe's CBDC Designers Wrestle With Privacy Issues, Coindesk. https://www.coindesk.com/policy/2022/04/04/europes-cbdc-designers-wrestle-with-privacy-issues; Middleton, P. (April 29, 2022). How Real is the CBDC Threat to Privacy? Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum. https://www.omfif.org/2022/04/how-real-is-the-cbdc-threat-to-privacy.

31. Tsang et al (2022), pp. 4-5.

32. An ECB public consultation showed that 43% of public respondents felt that privacy is the most crucial feature of the digital euro. European Central Bank. (2021). Eurosystem report on the public consultation on a digital euro. Accessed March 27, 2023, from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/Eurosystem_report_on_the_public_consultation_on_a_digital_euro~539fa8cd8d.en.pdf, p. 10-11.

33. Eurogroup (2023).

34. Digital Euro Association. (2022). CBDC Manifesto. Accessed March 25, 2023, from https://cbdcmanifesto.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/20221011-CBDC-Manifesto-final.pdf.

35. Gross, J., Sedlmeir, J., Babel, M., Bechtel, A., & Schellinger, B. (2021). Designing a central bank digital currency with support for cash-like privacy.

36. Transactions can still be linked to users' identities as a result of subsequent investigations, usually by judicial authorities. Electronic payments leave traces when an Internet connection is required for execution. If necessary, additional techniques can be used to provide additional confidentiality. See, for example, European Central Bank and Bank of Japan, Balancing confidentiality and auditability in a distributed ledger environment (February 2020). Accessed March 27, 2023, from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/paym/intro/publications/pdf/ecb.miptopical200212.en.pdf.

37. European Central Bank. (2020). Report on a digital euro. Accessed March 27, 2023, from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/Report_on_a_digital_euro~4d7268b458.en.pdf, p. 27; Eurogroup (2023), supra note 28; Panetta, F. A digital euro that serves the needs of the public: striking the right balance. Introductory statement at the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European Parliament. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2022/html/ecb.sp220330_1~f9fa9a6137.en.html.

38. Panetta, F. A digital euro that serves the needs of the public: striking the right balance. Introductory statement at the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European Parliament. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2022/html/ecb.sp220330_1~f9fa9a6137.en.html